A modello for the monumental high-relief of the SS Pasteur

On June 9, 1980, sank the Filipina Saudia, off the coast of the Indian Ocean. This forty-year-old liner, which had left Jeddah to reach Manila, had had an eventful life and many owners. The Filipina Saudia I had been named so when it was acquired in 1976. Before, it was known as the Regina Magna ; but Regina Magna was not the real name of the ship. It had been named this way five years earlier, in 1971, upon its acquisition by the Greek shipowner Chandris. But what Chandris had bought that year was a ship called the Bremen, and ‘Bremen’ was a name that had been given in 1957 by the Norddeutscher Lloyd to a truly mythical ship : the Pasteur.

The SS Pasteur, a French liner 695 ft long, 87 ft wide, capable of carrying at least 26,500 tons, with 50,000 HP to cross the South Atlantic with 850 passengers on board, at a service speed of 22.5 knots. On her maiden voyage, the Pasteur was set to sail for Buenos Aires. Departure was planned on 14 September 1939. But the war prevented her from doing so : in August 1939, she returned to Saint-Nazaire to be transformed. Nearly a year later, after the German invasion of May 1940, she left for Brest. There she was loaded with a large quantity of gold, 213 tons from the vaults of the Banque de France, to be delivered to Halifax. After Halifax, she sailed to New York, to be loaded with weapons and ammunition, and sailed back to Halifax. This is when the British took control of her. They sent her to England. There, she was transformed a second time, to carry troops. Now a trooper, the former liner travelled between Southampton and Quebec. She also brought reinforcements to Suez after the German assault on El Alamein.

After returning under French control in October 1945, there was nothing left, of course, of the luxurious facilities that had made the fame of the Pasteur and those who designed her. Her once revered swimming pool, which before the war had featured in many advertisements and magazines, was then used to store soldiers’ rations. And even after the war the Pasteur kept sailing the Atlantic and Indian oceans. She made stops in Indochina and Africa until 1957. This is when she was sold, painfully and with some scandals, by the French government, looking for savings and for liquidity. The Pasteur was then acquired by Norddeutscher Lloyd, now Hapag-Lloyd, and became the Bremen.

In the months leading up to her inauguration, the Pasteur's first trip was advertised at great expense in the major magazines and newspapers. One article of Le Temps said that :

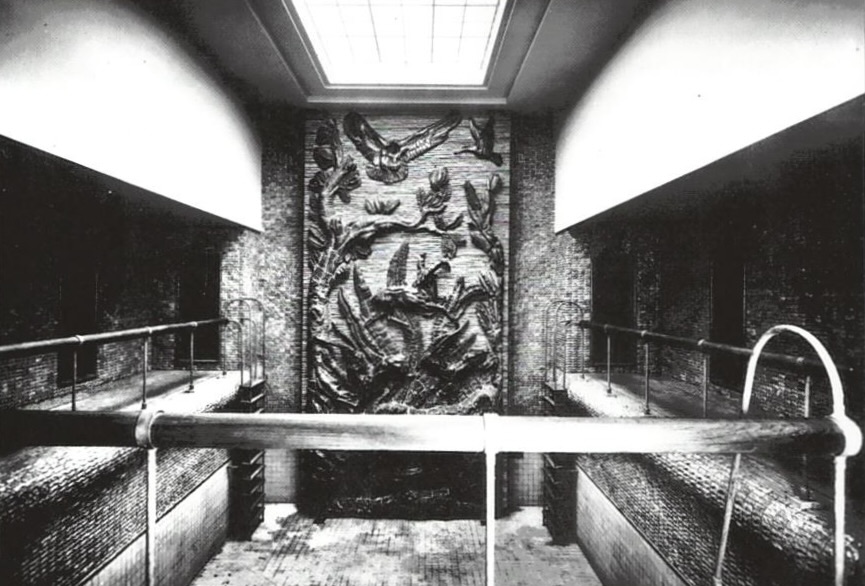

Passengers will find all the comfort they need : a library with thousands of books, an orchestra, movie screenings and ballrooms. Sports were particularly thought about on a ship set to sail under a heavenly climate and calm weather. An entire deck, 425 ft long, has been dedicated to sports, including a tennis court, all possible deck games, a bar and a lounge — perhaps the most successful innovation on board. Covered in raffia and bleached hemp rope, with 54 picture windows opening directly onto the sea, it is a real floating club. A dedicated staircase connects the lounge to the rooms of mechanotherapy and hydrotherapy, and to a superb swimming pool, adorned with a large 23 ft high decorative ceramic panel by Mayodon.

Designed by the architects Maillard and Raguenet, the Pasteur was meant to be a sumptuous, lavish, almost paroxysmal enterprise : lightings by Perzel and Ingrand, ironwork by Subes, furniture by Majorelle and Leuleu, and — last but not least — a gigantic swimming pool (fig. 3) designed by Georges Hennequin and enhanced by a monumental bas-relief by Jean Mayodon, one of the greatest ceramists of his time.

About the swimming pool, Raymond Lestonnat, the ‘naval pundit’ of the leading weekly publication L’Illustration, wrote :

And what about the pool ? True magic. Lit up with diffused light, a submarine light, so to speak. The walls and floor are covered with glazed stone. Two terraces with a view on the sea, connected to the pool so the bathers can grab a drink at the bar without having to walk by the clothed tourists of the deck. Even the great and fashionable resorts are not so well equipped.

Jean Mayodon already a well-known ceramist when he was chosen to decorate the Pasteur’s swimming pool, famous especially for his ‘rich bestiary’ of swans, peacocks, horses, lions, gazelles. He had exhibited at most major shows, including the Salon d’Automne and the Palais Galliera. He was also a rising star at the prestigious Manufacture de Sèvres.

Born in 1893, Jean Mayodon began his career as a painter, and a painter he never ceased to be. An art critic, Ernest Tisserand, wrote in 1928 : ‘Apart from the fact that Mayodon, for ten years of his life, was almost exclusively concerned with painting on canvas, he reveals himself, in all his current works, as the only painter of frescoes that we have today’. Jean Mayodon himself confirmed this painter’s spirit in an interview quoted by Gérard Landrot : ‘I still have in my hand all the drawings and ornaments I used to do when I was a decorative painter. I love nudes and animals, and above all gaudy colours.’

It was around the age of 19, in 1912, that Mayodon began to work with ceramics. He was so evidently gifted that decorative artist Henri Hamm noticed him the very same year, and helped him exhibit his first works at the Salon d’Automne.

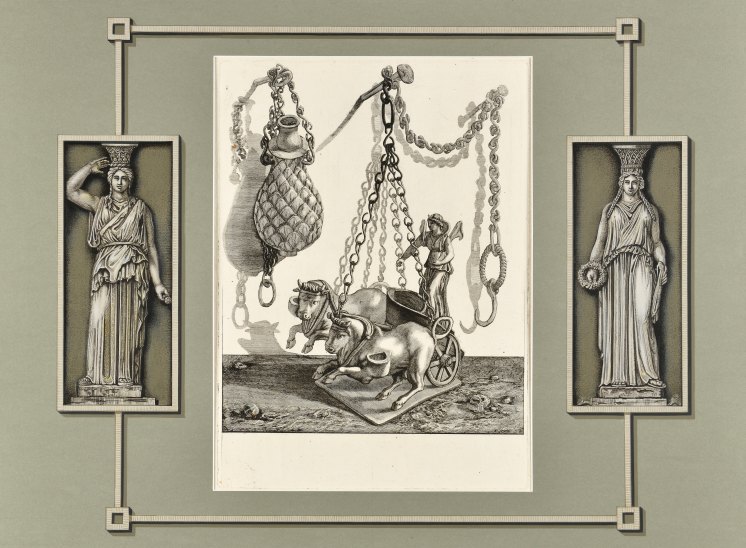

Mayodon's fame in the 1920s was mainly due to his iconic vases, colourful and often gilt, with shapes inspired by Greek red-figure ceramics. At the time, Jean Mayodon was, so to speak, the leading ceramist to whom the greatest architects and decorators of the period turned, from Jules Leleu to Ruhlmann, not forgetting Porteneuve, Subes and Printz.

At the beginning of the 1930s, when he designed his first sketches for the huge bas-relief of the Pasteur — most likely in 1935 — Mayodon was somehow still rising : the Manufacture de Sèvres, undoubtedly the most famous porcelain factory in Europe since it was founded in 1756 — where he had trained under Ambroise Milet, and of which he would become artistic director in 1941 — had taken him onto its prestigious artistic board a year earlier, in 1934. But it was also, for Jean Mayodon, what could be said his ‘monumental period’ : once a decorative artist, who had crafted sumptuous but discreet pieces chosen to enhance interiors designed by great architects, Mayodon was now creating immense sculptures, works of fine art that, while still designed to fit into carefully designed interiors, could now have a life of their own and exist for their own sake. Between 1931 and 1938, Mayodon produced several monumental panels and reliefs : a large relief for the Dubly apartment, decorated by Ruhlmann ; the large relief for the Golden Age in 1936 ; and another large relief, with several panels, for the World’s Fair 1937. In other words, Jean Mayodon was clearly an artist at his technical acme when he agreed to supply the monumental relief for the Pasteur’s, and designed the Antilocapra modello.

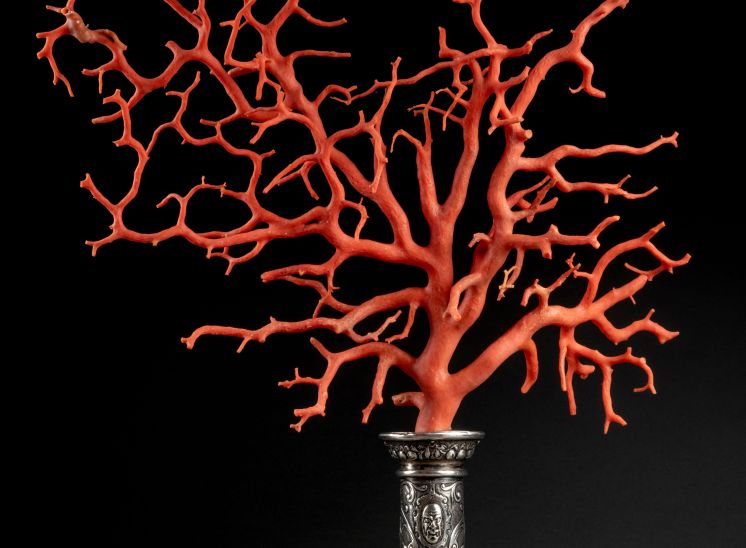

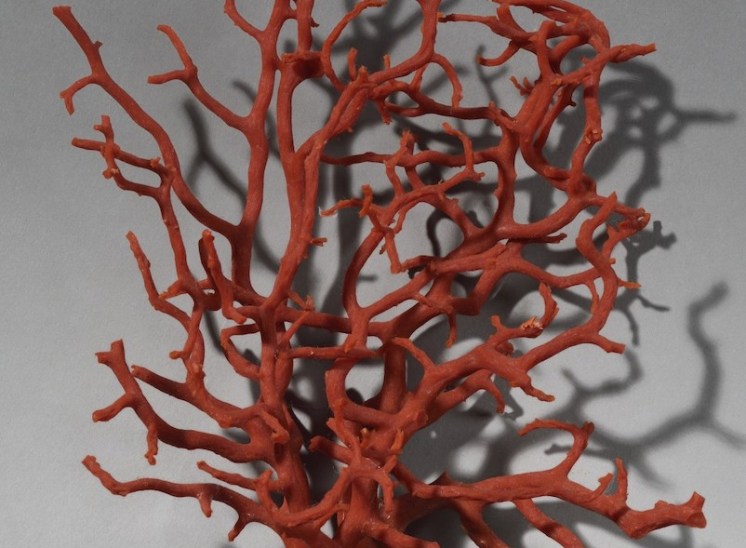

The monumental haut-relief of Le Pasteur, baked in a large fire, is 30 ft high (a total of 23 ft according to the article in Le Temps, which probably does not include the underwater part of the relief, cf. pl. I), and had as its subject the flora and fauna of South America. The composition was bronze-green against a background of beige to pinkish red, a colour chosen by the architect Georges Hennequin, who had undertaken to line the walls of the pool with terracotta bricks. Now lost — no one knows if it was dismantled or destroyed during one of the Pasteur's many conversions, or if it sank with the ship in 1980 — nothing remains of Mayodon's masterpiece, apart from the illustrations (fig. 3) and photographs (pl. II) of the pool ; and apart, of course, from the prototypes designed by the artist in the years leading up to the Pasteur’s inauguration.

This modello, representing an earlier version of the final high relief, is therefore one of the last remnants of what is perhaps the masterpiece of one of the greatest ceramists of the 20th century. Very similar in style and technique to the large Hunting Scene on held at the Musée Despiau-Wlérick in Mont-de-Marsan, this modello came from a private collection, where it was held for over 20 years. It previously belonged to the Mayodon family, having been in Jean Mayodon’s personal collection from at least 1938 until his death in 1967.

Sources

Ernest Tisserand, « Mayodon, Jean. Peintre et céramiste », in L’Art et les artistes. Revue mensuelle d'art ancien et moderne, Paris, 1928.

Le Temps, « Le Paquebot « Pasteur » », August 29, 1939.

Le Monde, « Sous le nom de « Bremen », la troisième unité de notre flotte concurrencera l’ « Île-de-France » sur l’Atlantique », July 19, 1957.

Le Monde, « Le « Pasteur » est arrivé à Brême », Octobre 1st, 1957.

Le Monde, « Première escale d’un transatlantique allemand en France depuis dix-neuf ans », July 26, 1958.

Gérard Landrot, Mayodon, Luxembourg, 2004.

Judith Miller, Art Deco, London, 2005.

Frédéric Ollivier, Aymeric Perroy and Franck Sénant, À Bord des paquebots. 50 ans d’arts décoratifs, Paris, 2011.

Olivier Le Bihan, Céramique d’artiste. Derain, Dufy, Matisse, Miró, Picasso…, Milano, 2012.

Nicole Blondel, Céramique. Vocabulaire technique, Paris, 2014.

Le Monde, « Philatélie : Grande Armée, guerre de 1870-1871, 1 franc vermillon, « Paquebot Pasteur », pièces vedettes des prochaines ventes », May 19, 2019.